You’d assume by now that we know our bodies pretty well and that, in the world of science, we’d know everything about our biology.

But apparently not. Even in the bodies we live in every single day there’s still more to discover.

And not just a little spot either, I’m talking discovering a whole new organ.

That’s exactly what a team of researchers from the Netherlands did when they figured out we had a whole other organ back in September 2020, and they discovered it entirely by accident while studying prostate cancer.

It turns out this hidden organ was right under our noses this whole time, or more accurately, just behind it.

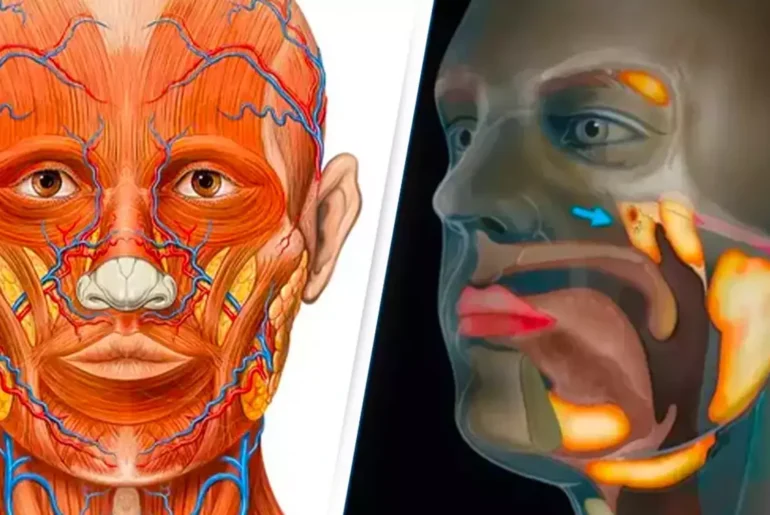

That’s right, it is actually located inside our own head, just beneath the face.

At this point, you may be wondering how a team studying prostate cancer ends up discovering an organ in the human head, considering those are two different ends of the body.

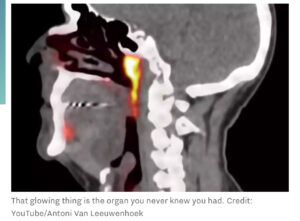

It all went down after the scientists studying the cancer conducted a series of CT and PET scans on patients injected with radioactive glucose that makes tumours glow on the scans.

The team at the Netherlands Cancer Institute realised that two areas within the heads of the patients were lighting up an awful lot and figured out that a set of salivary glands were tucked away in there.

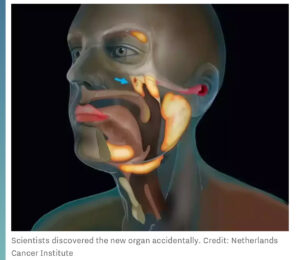

The discoverers named the organ the tubarial salivary glands, and to be precise about their location, they can be found behind the nose; in the nook where the nasal cavity meets the throat.

As for what this accidentally discovered organ does, they’re supposed to ‘lubricate and moisten the area of the throat behind the nose and mouth’.

The discovery of the glands came as a shock to the scientists, leaving the experts confounded as to how they were somehow able to remain undetected for so long.

Dr Wouter Vogel, radiation oncologist at the Netherlands Cancer Institute, said the most likely reasons they have stayed hidden this long are because it takes ‘very sensitive imaging’ to spot them and they’re ‘not very accessible’.

He said: “People have three sets of large salivary glands, but not there.

“As far as we knew, the only salivary or mucous glands in the nasopharynx are microscopically small, and up to 1,000 are evenly spread out throughout the mucosa. So, imagine our surprise when we found these.”

Discovering this organ could help explain why people who are given radiotherapy treatment tend to suffer from a dry mouth and problems with swallowing afterwards.

Dr Vogel said a ‘single misdirected zap’ could permanently damage the organ, and not knowing they existed meant that ‘nobody ever tried to spare them’ before.

Although the discovery was accidental, scientists hope in time their findings will help cancer patients experience less complications after receiving radiotherapy, as they believe many complications surrounding the treatment are connected to the tubarial salivary glands.

Now they know about this organ, the ‘next step’ is figuring out how not to damage them during radiotherapy treatment.

If the experts can crack that one, it could result in a significant boost in the quality of life of people who require radiotherapy.